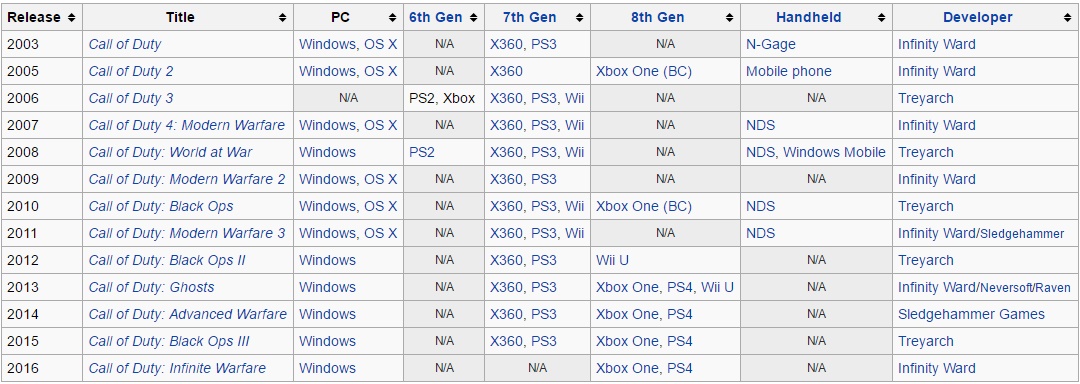

When I was younger, when a game was released, the only payment a player would be responsible for was buying the disc. However, as I began to play more mature games like Call of Duty, I noticed that a few times per year there would be DLC (Downloadable Content) releases in which new maps would be released. While purchasing these releases was not mandatory, those that did not purchase the DLC maps would not be able to play with those who did purchase them, essentially splitting the player base in half. I always did purchase the DLC maps as they weren’t too expensive and I looked forward to new in-game content. While the Call of Duty franchise was not the first game to include in-game purchases, my experience with Downloadable Content first came while playing COD and games released by EA Sports such as NHL and FIFA.

Although the splitting up of the player base in Call of Duty was irritating, a player’s in-game performance was never directly influenced by anything that was available for purchase. That is, until they decided to release “supply drops” in 2014’s Advanced Warfare. Supply drops were initially earned in game; these drops included variants of weapons that provided players with a distinct advantage, as many variants included increased damage and range or significant improvements in mobility speed. While the release of supply drops received a bit more backlash than Activision (developers of Call of Duty) expected, because supply drops were originally not available to be purchased, the backlash was limited. However, Activision ultimately decided to release advanced supply drops which were available for purchase and provided significantly higher odds of obtaining the best weapons in the game.

(Call of Duty Advanced Warfare unfair weapon variant and Advanced Supply Drops in the Marketplace)

Unlike the original supply drops, this move by Activision caused extreme damage to the game, as many players felt that the integrity of the game had been lost. Now, the skill gap was smaller, and the game became “pay to win.” Although I think the community overreacted to these supply drops since the weapons weren’t that much better than the originals, Call of Duty’s player base began to decline at a rapid rate. Call of Duty seemed as though it would be a dead game so long as supply drops and microtransactions were a part of the game. To combat this issue, Activision made supply drops that include strictly cosmetic items that did not impact game performance. Although this change was positive, Call of Duty has never been the same game as it was when microtransactions were limited to DLC maps.

While Call of Duty may have ruined the game by way of microtransactions, one game that enhanced the player experience through the use of microtransactions is CS:GO. CS:GO also allows players to purchase skins for real money; however, these skins hold monetary value and can even be resold on the marketplace. Through microtransactions, CS:GO has not only preserved the longevity of their game, but also created an entire community of players who are obsessed with collecting and trading. While no game that includes microtransactions will ever be perfect in my opinion, I think CS:GO does an amazing job of integrating microtransactions as an optional enhancement to game enjoyment. Some of these skins have even gone on to sell for tens of thousands of dollars, even hitting prices well over $100,000.

(This CS:GO knife skin is valued at over $1 million, and its owner has turned down offers over this price tag)

While my complaints regarding microtransactions seem to be very minor as they only affected my enjoyment of the game, there are more tangible reasons as to why microtransactions are more harmful than good. One thing I have noticed in microtransactions is that there are two specific types, both of which ruin the experience: microtransactions that provide an advantage or those that look to exploit children.

In my experience of playing games, since Call of Duty, I have mostly seen the first type of microtransactions in sports games, specifically FIFA. For example, when I was in high school, I watched one of my good friends become addicted to opening FIFA Ultimate Team packs just to gain an advantage against other players. When it was all said and done, he had spent around $2,000 in under 6 months, causing a long discussion with his parents. Again, microtransactions of this type may be annoying to those that do not wish to spend money, yet they can also be extremely problematic to individuals, especially when the perceived in-game advantage they provide is extremely large as is the case with FIFA.

For the second type of microtransactions I have come across, the first game I point to is Fortnite. Although the items offered in the Fortnite marketplace do not affect gameplay, the inclusion of pop culture icons and characters in game “skins” is directed at mainly children, especially when considering Fortnite’s player base. While this may be profitable for the developers of Fortnite, it begs the question: are microtransactions truly ethical? When purchasing from the Fortnite marketplace, it takes about 15 seconds for an individual to add money to their account and purchase a new skin. And with each skin costing roughly $15-$20, purchasing skins quickly becomes a very expensive hobby that young kids are most likely unable to stop themselves from participating in. Considering that the revenue from microtransactions is nearly $100 billion per year, I would argue microtransactions in this context are absolutely not ethical; however, there is no chance that microtransactions are going anywhere, as they’re just too profitable.

(Fortnite marketplace featuring Star Wars skins for purchase)

As mentioned previously, microtransactions can be positive for a game; however, they also cause a lot of problems when overused and when they’re meant to exploit young kids. In the days of early Call of Duty and CS:GO, I thought microtransactions could help enhance games; yet, when a game revolves around its microtransactions, I learned how microtransactions could become exploitative and lead games to lose their integrity. While I’m not exactly sure how to fix this issue, I do think we need to investigate solutions, as it is typically more of a problem than a game enhancement.

You must be logged in to post a comment.