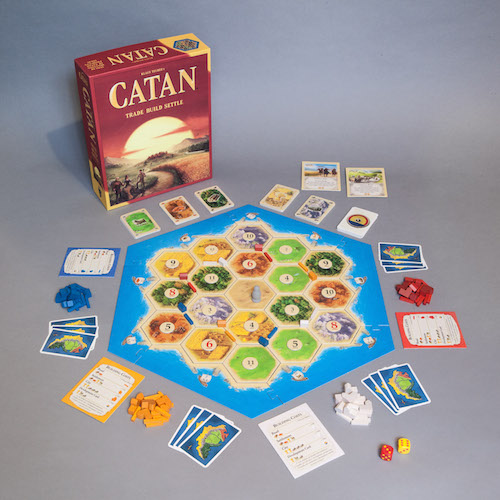

Catan is my favorite board game. The game is a beautiful combination of probability and statistics, luck, and careful strategizing. It’s an open-ended exploration and building competition, where the procedures of play make ample space for players to create their own individual and group narratives.

I will now give a simple overview of the base Catan game gameplay before I explore my personal passion, which is the Cities and Knights expansion game. Please note I am omitting key details necessary for play, this is just an overview. Full rules can be found here.

To start, each player puts two settlements with a road attached (see below) on the intersecting corners of hexagons which are set randomly each game. The first player rolls the dice, which corresponds to the numbers on each hexagon—a unique board is created every time as far as location of resource hexagons, but the numbers are in a set order to diversify the board. More dots means that number has a higher statistical probability, and the red numbers are the two highest probability numbers on the board (6 and 8). Something different happens when a 7 is rolled—refer to the game rules.

After the roll, which starts each turn, each player with a settlement on a hexagon marked with the number rolled receives a resource card or multiple: Wood, Brick, Sheep, Grain, and/or Ore. Throughout the game, the players trade resources to get what they need so they can build more roads, settlements, and upgrade their existing settlements to cities by paying the bank, acquiring more points until the winner has 10: a settlement is 1 victory point and a city is 2. Players can also purchase a development card (Figure x) which gives them opportunities for progression in the game.

This game, to put it bluntly, was my entire quarantine. It made the time holed up at home not only bearable, but magnificently wonderful and inspiring. Playing with my loved ones was my favorite part of this unprecedented Summer of 2020, and mainly because of the Catan expansion Cities and Knights.

This game complicates and expands upon the base Catan game in many ways. Players set up one settlement and next a city during the set-up phase. Each city yields a resource and commodity when a number a city is on is rolled, in the case of wood, ore, and sheep. When a number with a city on wood, ore, or sheep is rolled, that player receives a Wood and a Paper, an Ore and a Coin, and/or a Sheep and a Cloth respectively. Brick and Wheat still receive two resource yields with a city.

There is a third event die introduced into the game that adds significant gameplay. When a black ship is rolled (the most probable outcome) the Barbarians move closer to the island of Catan. Before the Barbarians arrive at the shore, there needs to be at least one activated knight per city on the board. If there aren’t as many activated knights as cities, the player who contributed the least number of activated knights replaces a city with a settlement. This is the knight system with the Expansion (different from the base game, read the rules here). Knights are often key in winning the game—tying with another player in a victory against the Barbarians allows both players to select a special progress card, while having more than other players grants that player a victory point.

The third event die introduced into the game allows players to get the special progress cards for Cities and Knights. These are unlocked by purchase flips that represent city upgrades, bought with commodities (1 commodity for first flip of each kind, 2 for 2nd, etc.). With the third flip for each category, Trade, Politics, and Science, there are special benefits. The best in my opinion is the Aqueduct on the right, as it brings in consistent yield during play. The first person to get the fourth flip for each category gets a Metropolis (see below) which is an additional 2 points, and is worth another city that needs protecting with an activated knight against the barbarians.

If a certain combination of colored event die and the number on the red die is met (as outlined on each card above, circled in blue), you get a special development card for either Politics (blue, Ore/Coin), Trade (yellow, Sheep/Cloth), or Science (green, Wood/Paper).

Here are some examples of the new special progress cards; I’d highly recommend reading these to get a taste of the game!

Cities and Knights, even more so than the base Catan game, creates a space where the physical mechanics and procedures make for an extremely interesting basis for personal and interpersonal narrative creation. Each player can use a myriad of progress cards during any given game, helping players to visualize themselves as a scientist, lord of war, and/or master of trade. The game is political—players will convince their opponents to engage or not engage in certain trades or moves with their own personal interest in mind. The climax comes when a player wins, earning the respect of their opponents. Cities and Knights expands upon the base Catan game in numerous ways and I definitely recommend it for fun-filled adventures at home. The gorgeous art of the Catan game shines through on the table, with added opportunities to meddle in your enemies’ business and build up your society. As I’ve learned, Catan rivalries run deep…

Cities and Knights costs $40, in addition to $40 for the base Catan game, and an additional $50 to be able to play both with more than four players—Catan, sadly, is not cheap. I wish the board games themselves were more accessible for people to play, though I have linked some online versions below.

Additional Reading

I referenced a helpful overview of the Catan base came, which can be accessed at: https://www.catan.com/game/catan

Full base Catan game and Cities and Knights rules can be found here (referenced throughout article). Reading these will be necessary to play the game if you don’t already know all the rules: https://www.catan.com/service/game-rules

There is also a Catan Universe app, which is quite fun—you get to create an Avatar, which I always enjoy. Players can unlock unlimited games and the Cities and Knights by paying some money.

Online knock-off Catan can be found at colonist.io. A good socially distant option for during the Pandemic, players can play with friends or strangers. Though, the art is not as beautiful as Catan and it simply isn’t the same. The mechanics of the game get muddled in the process of clicks it takes to do anything.

You must be logged in to post a comment.